The environmental changes of glacial periods greatly influenced the evolution and present-day distribution of terrestrial and aquatic species. Most populations persisted in glacial refugia -ice-free areas from which they began to colonise northern regions as environmental conditions improved during post-glacial periods. In addition to influencing species distribution, these climatic changes shaped species ecology, in some cases leading to shifts in diet, habitat, and behaviour. While these patterns have been extensively studied for terrestrial species during the last glacial period (26.5 – 19 kya), the same is not true for aquatic ecosystems. Yet thousands of fossils of fish, particularly salmonids, have been found at numerous Palaeolithic archaeological sites across Europe.

Understanding how the last glacial period impacted the phenotypic diversity of brown trout (Salmo trutta Linnaeus 1758), a species of salmonid with vast phenotypic diversity and adaptive capacity, might provide insights into fish ecology and evolution, the impact of past climate changes on intraspecific biodiversity, and human reliance on fish resources in the past. Brown trout is a facultative anadromous species, which means that individuals with very different life cycles co-exist within the same population: some migrate to the sea (or estuary, lake) during maturation (migratory individuals, aka anadromous if they migrate at sea) and then return to the river for reproduction, while others remain and grow in freshwater (resident brown trout). These two different strategies involve phenotypic changes in colour, diet and size and have consequences for survival. For example, while migration entails risks for the survival of the individual, it increases reproductive success (a higher growth rate can lead to greater fertility, especially in females). Resident trout growth rates are usually lower, but survival is less at risk. The presence of both strategies is advantageous for the survival of the species, which can thus exploit different environments and colonise new habitats through migration. Studying this aspect of brown trout is therefore crucial in an exceptional context such as the ice age. Together with migratory status, growth rate is another noteworthy phenotypic feature, correlated to the individual’s health, migratory status and fertility. The growth rate of brown trout strongly depends on temperature, which thus also modulates the age at migration. During the ice sheet maximum extension between 26 and 19 kyr B.P., lower temperatures might have determined reduced growth rates in brown trout and, in general, lower productivity in the ecosystem.

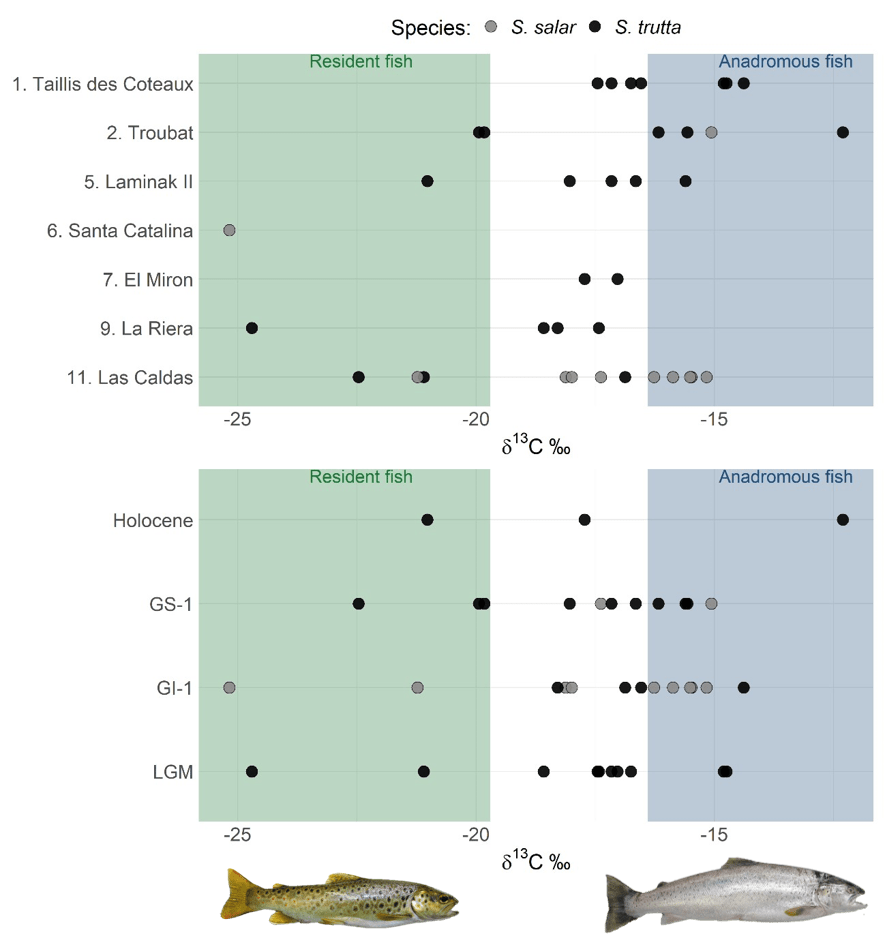

To reconstruct these aspects of the phenotypic diversity of S. trutta, we studied brown trout archaeological vertebrae dating back to approximately 30–9 kya, found in the northern part of the Iberian glacial refuge (northern Spain and France up to the Loire). This sampling allowed the study of phenotypic variation over time (pre-, during, and post-LGM) and space (the core of the refugium, Spain, and north of the refugium, France). The inference of migratory status using the stable isotope carbon-13 (which has differential values in marine and freshwater environments) showed a continuum of migratory strategies throughout the studied period. Together with migratory individuals displaying a classic anadromous life cycle and resident individuals, several fish with intermediate signatures were found. We interpreted these as fish that either spent a variable period in freshwater before and/or after sea migration, behaviour also observed today, or migrated to low-salinity regions, such as estuaries or the English Channel during post-LGM.

Age, body length, and average growth rates, calculated through vertebrae size and sclerochronology, fell within the range observed for contemporary brown trout populations.

Overall, the results demonstrated brown trout acclimation to the climate changes of the last glacial maximum, confirming the adaptation capacity of the species to low temperatures and the role of Iberia in maintaining its diversity. Moreover, the persistence of the migration capacity implies that these populations could have potentially colonised the northern regions of Europe after deglaciation.

As a last thing, this study suggests that the inland regions of France were more affected by the shift in the climatic conditions as brown trout showed significantly lower growth rates in this region during the LGM and no resident brown trout was found in the northernmost archaeological site in France (Taillis Des Coteaux), possibly indicating harsh local conditions pushing the individuals to migrate to sea, which is usually less sensitive to climatic changes than river habitats.

Take-home message: The phenotypic diversity of brown trout during the last glacial maximum in the Iberian glacial refugium was maintained and comparable to the current one.

References

Ambra D’Aurelio, Lucía Agudo Pérez, Lawrence G. Straus, Manuel R. González Morales, Arturo Morales-Muñiz, Jerome Primault, Jean-Marc Roussel, Laurence Tissot, Stephane Glise, Frederic Lange, Camille Riquier, Michel Barbaza, Eduardo Berganza, José Luis Arribas, Pablo Arias, Aurélien Simonet, Ana B. Marín-Arroyo, Joelle Chat, Françoise Daverat (2025). Phenotypic diversity of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) during the late Upper Pleistocene and Early Holocene in the glacial refugium of Iberia,

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, Volume 675, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2025.113073

Clark, P. U., Dyke, A. S., Shakun, J. D., Carlson, A. E., Clark, J., Wohlarth, B., Mitrovica, J. X., Hostetler, S. W., & McCabe, A. M. (2009). The Last Glacial Maximum. Science, 710–714.

Ferguson, A., Reed, T. E., Cross, T. F., McGinnity, P., & Prodöhl, P. A. (2019). Anadromy, potamodromy and residency in brown trout Salmo trutta: The role of genes and the environment. Journal of Fish Biology, 95(3), 692–718. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.14005

Hewitt, G. (2000). The genetic legacy of the Quaternary ice ages. Nature, 405(6789), 907–913. https://doi.org/10.1038/35016000

Ménot, G., Bard, E., Rostek, F., Weijers, J. W. H., Hopmans, E. C., Schouten, S., & Damsté, J. S. S. (2006). Early Reactivation of European Rivers During the Last Deglaciation. Science, 313(5793), 1623–1625. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1130511

Nevoux, M., Finstad, B., Davidsen, J. G., Finlay, R., Josset, Q., Poole, R., Höjesjö, J., Aarestrup, K., Persson, L., Tolvanen, O., & Jonsson, B. (2019). Environmental influences on life history strategies in partially anadromous brown trout (Salmo trutta, Salmonidae). Fish and Fisheries, 20(6), 1051–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12396